'Frankenstein' and Polar Exploration, Part I

The two Arctic expeditions of 1818--one fictitious, one real

If you’re just joining us, on Salvage here I’m focused on the ways very old literature has influenced our technological vision; and I originally turned to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to show the form of the romance, a literary genre that’s had an outsized effect on the modern technological imagination. Also, recall that the romance, as a genre, is not so much concerned with buxom beauties swooning in the arms of Fabio-looking dudes as with adventure beyond the limits of the protagonist’s society’s knowledge. The hero/ine of the romance enters the weird, the space beyond the edge of the map, encounters monsters and wonders there, and returns, changed, to tell the tale, hopefully bearing some proof that the story is true. The romance thus functions as a new installment on a previously-less-complete map. With proof, the hero/ine’s story is taken to be true, then it’s added to what’s known back home about the outside world.

On 1 January 1818, an anonymous writer published a gothic story called Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. The book was received with some consternation, with one of the harshest reviews coming from John Wilson Croker of the The Quarterly Review. Croker called the book “a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity” and, focusing on its author’s dedication to the novelist and political theorist William Godwin, Croker surmised that the author of Frankenstein was insane. Godwin’s disciples, Croker opined, “are a kind of out-pensioners of Bedlam, and… are occasionally visited with paroxysms of genius and fits of expression, which make sober-minded people wonder and shudder.”1 In a parting shot calculated to impugn the book beyond recovery amid Britain’s moralistic early-nineteenth-century culture, Croker griped—using the royal “we,” no less—that

Our taste and our judgment alike revolt at this kind of writing, and the greater the ability with which it may be executed the worse it is—it inculcates no lesson of conduct, manners, or morality; it cannot mend, and will not even amuse its readers, unless their taste have [sic] been deplorably vitiated—it fatigues the feelings without interesting the understanding; it gratuitously harasses the heart, and wantonly adds to the store, already too great, of painful sensations.2

In other words, Croker found the book mad, sensate, and amoral, but he allowed for the possibility that it was a work of literary genius.

Beyond his by-then-well-established reputation as a literary critic as one of The Quarterly Review’s founders, Croker’s perspective matters because he was also First Secretary of the British Admiralty, which was preparing an Arctic expedition in search of the Northwest Passage; and Frankenstein’s narrative frame is a polar expedition. The book opens with a correspondence from a young explorer, Robert Walton, who’s traveling through Russia with the design of hiring a ship at Archangel and sailing north into the Arctic in search of the North Pole. Walton is writing to his sister, Margaret, with a romantic fervor about his undertaking and what he imagines he’ll encounter in the weird beyond all knowledge, the margin at the top of the globe.

In the years leading up to Frankenstein’s publication several theories about what lay at the North Pole were competing for scientific authority. Some theories offered utopic visions of a place beyond the snow and ice, where the sun never sets. Referring to the cold winds of St. Petersburg, Walton writes:

Inspirited by this wind of promise, my day dreams [about the North Pole] become more fervent and vivid. I try in vain to be persuaded that the pole is the seat of frost and desolation; it ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight. There, Margaret, the sun is for ever visible; its broad disk just skirting the horizon, and diffusing a perpetual splendour. There—for with your leave, my sister, I will put some trust in preceding navigators—there snow and frost are banished; and, sailing over a calm sea, we may be wafted to a land surpassing in wonders and in beauty every region hitherto discovered on the habitable globe. Its productions and features may be without example, as the phænomena of the heavenly bodies undoubtedly are in those undiscovered solitudes. What may not be expected in a country of eternal light?3

(If you’ve been following my work here on Salvage you’ll notice that Walton describes his journey in terms of a romance like SGGK: he hopes to discover wonders beyond the boundary of the known world. But as we already know, he discovers a monster instead.)

Of course we know now there’s just a lot of frozen sea at the North Pole. Croker knew this even by early 1818 because he ridiculed the story’s plot: “The monster, finding himself hard pressed, resolves to fly to the most inaccessible point of the earth; and, as our Review had not yet enlightened mankind upon the real state of the North Pole, he directs his course thither as a sure place of solitude and security.”4 Croker, as we can see, was what I like to call “a trenchant realist,” the no-nonsense sort who today would dump on the idea that it’s possible to build a flying, AI-powered suit of armor, or the idea that there’s an alien portal in the Marianas Trench out of which may soon arise kaiju that can only be fought by humans driving giant battlemechs.

But neither Walton nor his author were so silly as to make the utopia at the North Pole the point of the story. Walton writes to Margaret that “you cannot contest the inestimable benefit which I shall confer on all mankind to the last generation, by discovering a passage near the pole to those countries, to reach which at present so many months are requisite; or by ascertaining the secret of the magnet, which, if at all possible, can only be effected by an undertaking such as mine.”5 Croker had no truck with these visions and so left them out of his review. (Best not to say anything too positive.) But a few months later, the Admiralty would set in motion a series of expeditions that would eventually discover both a route through the Canadian Arctic to the Bering Strait and the magnetic north pole. And it’s these expeditions I want to tell you the story of, starting with this post, because they show just how scientifically aware Mary Shelley was, which in turn establishes that Frankenstein, though a romance, as you might already have surmised, was also a work of what we would now call “science fiction,” though the term hadn’t been coined yet in 1818.

1818: John Ross’s First Voyage

I encountered this history of British polar exploration during a voyage of my own. In the Old Time before quarantine, universities funded their graduates amazingly well. When I discovered I needed to travel to an academic conference in Melbourne, Australia, I solicited funding from KU’s English Department to stay an extra week and do archive research. It was epic. I spent days in the archives at Melbourne Uni. and Sydney Uni., and there I found there a 200-year-old exploration story that ends in a real-life ghost story about lost ships, a bewildering trail of artifacts, and cannibalism, handed down through generations of Inuit in the Canadian Arctic. And The first few chapters of the story played out during the years 1818-1835—the decades during which Frankenstein was published, then revised, then republished.

Did you know that you don’t have to be a graduate student or a faculty member to do archive research? If you’re interested in learning about how anyone can use a university archive, DM me or leave a comment below. I’m considering a future post on the subject and your comments will help me gauge interest. In your comment, tell me: Which universities are near you? And what would you want to research if you could spend time in an archive?

In the archives at Sydney Uni. I ran across a book called The Ichthyology of the Voyage of the H.M.S. Erebus & Terror. At the time I was looking for the nineteenth-century roots of what I was calling “the mechanimal vision,” a nineteenth-century vision of future machines that would imitate animal bodies, particularly their movements. And as I later learned, the history of the explorations that eventually made the Erebus and Terror legendary begins with the expedition that Croker’s Admiralty launched in 1818. Shortly after Frankenstein was published, Captain John Ross set sail from London in the H.M.S. Isabella. His mission: locate, if he could, the Northwest Passage, a route through Canada’s Arctic by which British ships could feasibly sail to East Asia via the Bering Strait, rather than sailing around the southern tip of Africa.

As I mentioned in my previous post, “God’s Museum,” reading old texts helps us understand the context out of which a work of fiction arose. Consider how wide and scary the world must’ve felt when one of the fastest ways of traversing it was in a ship under sail—especially when people decided to try to sail through the polar ice packs.

In 1818, Ross set sail at the spring thaw because the Isabella had to cross the North Atlantic, sail through the Davis Strait and up the coast of Greenland, and then turn west into Lancaster Sound just as the warmest temperatures of summer rose. Even in summer, Lancaster Sound was an icy body of water and traversing it meant the crew sometimes had to debark and use picks to cut a channel through Arctic sea ice. Sometimes they had to trail lines overboard and walk on the ice, towing the ship by hand. Worse, across North America the weather pattern moves from west to east, which meant they had little help from the wind to reach ramming speed and cut through the ice; indeed, the wind often worked against them. To put it mildly, these guys were a breed of crazy that Bear Grills and Chuck Norris only dream of.

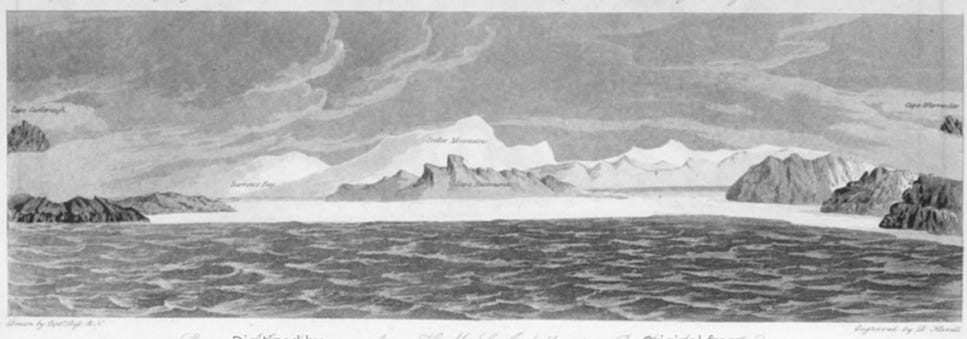

The Isabella passed what’s now the settlement of Resolute, on Cornwallis Island, late in summer 1818 and as Ross looked out, this is what he saw:

The grey landmass in the center of the sketch wasn’t the problem. The problem was the white-tipped mountain range behind it, which Ross named “Croker’s Mountains” after his favorite literary troll, John Wilson Croker. (Croker’s being First Secretary of the Admiralty might’ve had something to do with it as well.) Perhaps its fitting that these “mountains” turned out to be ephemeral gas clouds that only seemed to block the way for a bold new endeavor.

By the time Ross encountered “Croker’s Mountains” the season was late; supplies were low; the Isabella’s crew had already cut through hundreds of miles of polar ice; and they had a long way to go, either against the weather pattern through more polar ice and unfamiliar territory ahead, in hopes of reaching the Bering Strait, or back to England by way of the Davis Strait. Ross ordered a return east, the way they’d come.

At about where the orange dot appears on the map above, some of the Isabella’s officers began to question what Ross saw. Some contended that “Croker’s Mountains” were just a front of clouds. But since cameras were not yet a thing, Ross’s sketch is the only surviving record. The argument continued all the way home and when they arrived, one of the officers, Edward Sabine, who had the ear of the Second Secretary to the Admiralty, Sir John Barrow,6 sowed the notion that John Ross had squandered a golden opportunity.

Outraged, Barrow sidelined Ross; but Ross wasn’t done. He would go on to, as we now say, “frankenstein” a ship specifically for Arctic navigation. It was a bold attempt at engineering the naval future; and it failed spectacularly, as we’ll see next post.

Dr. Aaron M. Long is a Lecturer in English at a flagship state university, and a Lecturer in Philosophy at a historied regional art school. He has published articles in Twentieth-Century Literature, The Nautilus, and Science Fiction Film & Television, among others. Here on Substack he has collaborated on The Deadly Seven. You can find him on LinkedIn and his website is here.

John Wilson Croker, “From the Quarterly Review (January 1818),” in Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: The 1818 Text | Contexts | Criticism, Second Edition, ed. J. Paul Hunter (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co., 2012), 215-219; see pg. 218.

Croker, 218-219.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus [1818], eds. Charlotte Gordon and Charles E. Robinson (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2018), 8.

Croker, 217.

Shelley, 8.

Here “Second Secretary to the Admiralty” does not mean that Barrow was the second, following the first, which would’ve been Croker, mentioned above. At the time there were two Secretaries to the Admiralty. Croker was First Secretary, Barrow was Second Secretary.

I was not expecting the cliff hanger ending! This story just kept getting better.